I hope Kenya will emerge from the Uhuru-Ruto chaos intact

Saturday July 30 2022

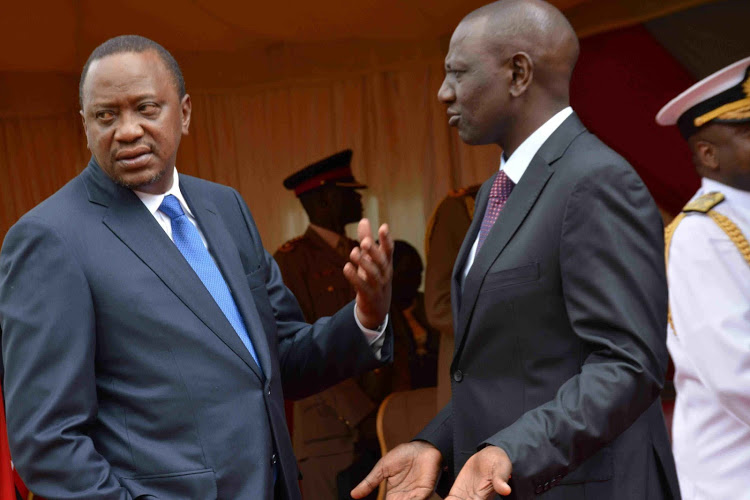

Kenya's president Uhuru Kenyatta and his deputy William Ruto at a past event. The two have been in unprecedented bare-knuckle brawls in public. FILE PHOTO | NMG

When Zambian president Frederick Chiluba threw his predecessor in jail in 1997, he was jerking up the relations between the two men to a new high. It had been going on for some time since the days before multiparty politics in the country. Kaunda was the head of state, and Chiluba was an uppity trade unionist wanting to challenge state authority.

Kaunda had given this pint-sized troublemaker a tour of jail a few times under the notorious preventive detention laws that many African rulers had armed themselves with to put out any dissent they faced.

Now the shoe was on the other foot, and Chiluba was anxious to use it as a boot to kick KK in the backside by making him taste a bit of his own medicine. To make it even tastier, he arrested him on Christmas Day, when any other day would have done just fine!

Julius Nyerere was so touched by this action and even more worried when his old friend went on a hunger strike that he asked for permission to visit KK in jail to convince him to eat. Chiluba allowed Nyerere to enter the jail, but on condition that the doors be locked behind him, lest KK escape!

This is an instructive story that informs politics on the African continent to this day. It has even come to cause thought to emerge within African governance discourses that it is the fear of being hunted down by their successors that renders many rulers refuse to vacate their offices once their terms come to an end. It has thus been suggested that there be some assurance or other that a former ruler will not be in any way made to account for his or her deeds when he or she was in office.

There have been other cases where new rulers have made those who ruled before them uncomfortable.

For instance, Botswana’s President Mokgweetsi Masisi is not on talking terms with Ian Khama for the simple reason that the latter supported an opposition candidate. Sierra Leone’s Ernest Koroma (former president) is not on the best terms with the man who replaced him, Julius Maada Bio.

South Africa’s Jacob Zuma has been jailed on the watch of his successor Cyril Ramaphosa.

Angola’s second president Jose Edouardo dos Santos went to his grave before being reconciled with the third president, Joao Lourenco.

And so on and so forth.

Even where there are no exterior signs of dissension, subterranean tremors suggest that all is not well.

In Tanzania, it is well known that John Pombe Magufuli’s histrionics did not sit well with Jakaya Kikwete or Benjamin Mkapa, though they hardly uttered a word to criticise him for the exactions he was meting out to sections of the population.

Samia would like us to believe she is following in Magufuli’s footsteps, though some of us are seeing parallel tracks in the sand.

All the tensions we have noticed on the African continent between the incumbents and those who went before them do have explanations, though some are not very clear, especially those occurring between two individuals emanating from the same political organisation, such as the case in Angola, South Africa or Tanzania.

Individual styles and personal predilections seem to have precedence over parties, especially because what are called parties are nothing but empty shells set up merely to grab state power.

It is over the resources of the country and how they will be shared among the various postulants that battle lines are drawn, and the cut-throat competition this causes can be deadly indeed, both before and after the contest is settled one way or the other.

It is in this context that I worry about the elections in Kenya early in August. The campaigns and their fallout have been most extraordinary. That a sitting president and his (also sitting) vice-president can be in a bare-knuckle brawl in the public is certainly unprecedented, and, for me, it augurs ill for the near future of the country, whoever wins in the contest.

To say that there is bad blood between Uhuru Kenyatta and William Ruto would be the understatement of the decade; the two literally hate each other’s guts, and they have let the world know as much. Their rivalry has made a number of people wonder how their government works nowadays, seeing as they are both still in office until the new government is installed. Just what is happening?

Much of the world observing this contest will be scratching their collective head trying to comprehend this scenario and what it portends for Kenyans. Some will ask whether the 2010 Constitution really helped the Kenyans to bury the devastating hatchet we saw in the wake of 2007-08 when mobs of Kenyans butchered and set fire to each other with such abandon that it seemed Armageddon had arrived.

As I say above, I know it is the resources of the country over which these unseemly wars are being fought. In the end, there will be a victor and a loser.

It is to be hoped that somewhere in the collective psyche, there will be enough forbearance and resilience to allow the Kenyans to emerge out of this apparent chaos with their sanity intact.